Table of contents

ToggleIntroduction

It took humanity thousands of years to evolve from barter to coins, from coins to paper money, and from paper to credit cards. Now, in just a few decades, we are on the verge of another revolution: the rise of digital currencies controlled by central banks. As technology reshapes how we trade, save, and invest, the very concept of money is undergoing a transformation more profound than any seen before.

Central Bank Digital Currencies, or CBDCs, represent the next frontier in monetary innovation. Unlike decentralized cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, these digital currencies are issued and regulated by national central banks, giving them the same legal status as traditional cash. They promise faster, cheaper, and more secure transactions while offering governments new tools for financial oversight and inclusion.

Yet this digital leap raises fundamental questions. Can a system built on code truly replace the tangible trust people associate with physical money? Will citizens accept a form of currency that exists only in digital form and may expose their every transaction to government scrutiny?

Across the world, countries are experimenting with answers. China’s e-CNY, the European Central Bank’s digital euro, and other pilot projects are testing not only technical systems but also the social and ethical boundaries of monetary control. As these initiatives expand, the debate intensifies: are CBDCs the natural evolution of money or the beginning of a cashless society where privacy becomes a luxury?

This article explores the origins, mechanics, and implications of CBDCs, examining whether they are destined to coexist with cash or eventually replace it altogether.

I. The Rise of Digital Money: From Cash to Code

1.1 The Decline of Physical Cash in a Digital World

The global economy has been moving steadily toward digitalization for over two decades. Today, fewer people carry coins or banknotes, preferring contactless cards, mobile payments, and online transfers. According to data from the Bank for International Settlements, the use of cash for transactions has dropped sharply in most advanced economies. In Sweden, for example, less than 10 percent of payments are now made in cash, while China has seen mobile platforms like Alipay and WeChat Pay become the default payment tools for hundreds of millions of users.

The pandemic accelerated this transformation. With health concerns discouraging physical contact, businesses and consumers adopted digital solutions at an unprecedented rate. Even small shops and local markets that once operated solely in cash began accepting QR codes and mobile payments. The shift was not just technological but cultural: cash, once a symbol of autonomy and security, started to appear outdated and inefficient in a hyperconnected world.

However, the disappearance of cash also creates dependence on private digital systems such as Visa, Mastercard, and fintech applications. These platforms, while convenient, place control of payment infrastructures in the hands of corporations rather than public institutions. This imbalance has fueled renewed interest among governments and central banks to reassert sovereignty over money through a public digital alternative.

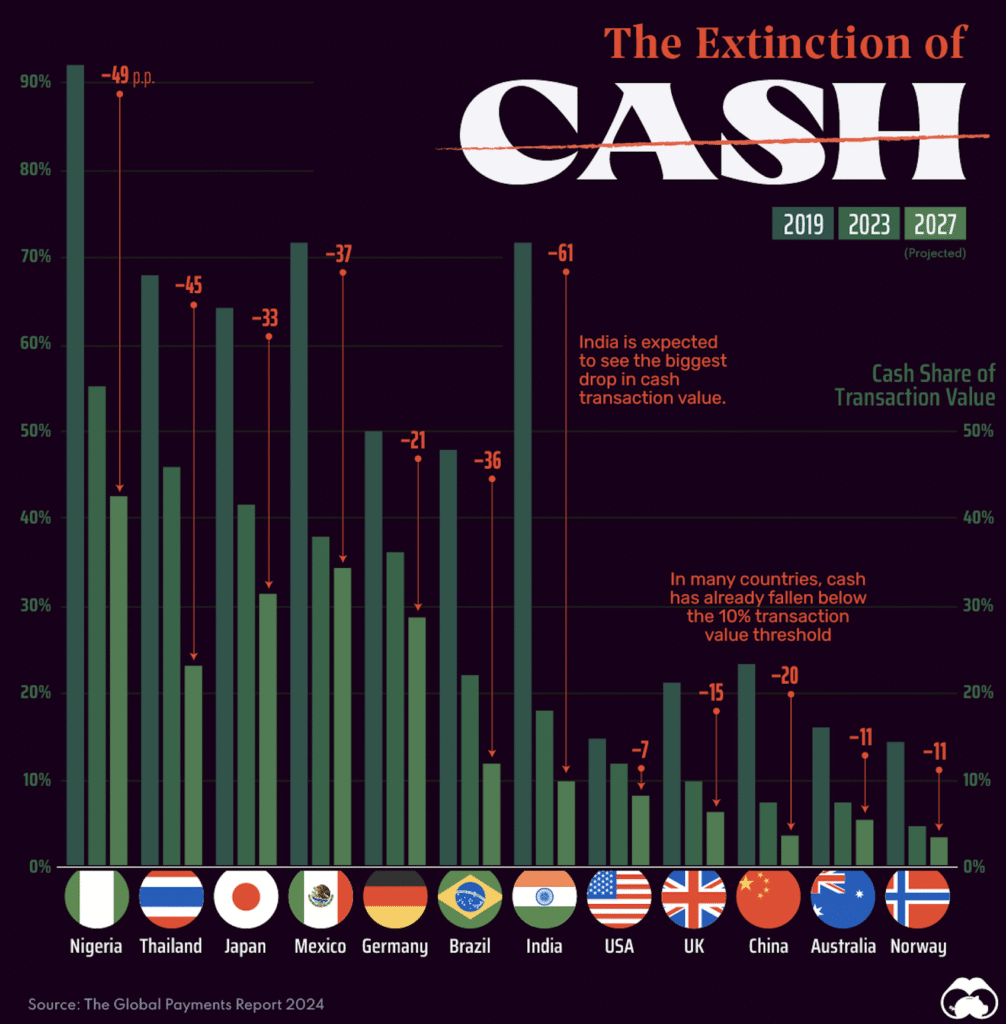

This transformation is evident when observing how rapidly cash transactions have declined across both developed and emerging economies over the past few years.

Cash usage is falling worldwide, with countries like India, China, and Sweden leading the transition to digital payments. According to The Global Payments Report 2024, several economies are projected to see cash transactions fall below 10 percent of total payment value by 2027.

1.2 The Birth of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs)

Central Bank Digital Currencies represent an attempt to merge the stability of traditional money with the efficiency of digital technology. A CBDC is essentially a digital version of a nation’s fiat currency, issued directly by the central bank. It functions as legal tender, just like cash, but exists purely in electronic form.

Unlike cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, which operate on decentralized networks without state control, CBDCs are centralized and backed by the full faith of their issuing governments. This distinction is crucial. Cryptocurrencies seek independence from financial authorities, while CBDCs aim to modernize and strengthen those same institutions.

Several central banks have already taken major steps in this direction. China’s digital yuan (e-CNY) is the most advanced example, already used in multiple pilot cities. The European Central Bank is progressing with its digital euro project, designed to ensure Europe’s monetary autonomy in an increasingly digital world. Meanwhile, countries like the Bahamas with their “Sand Dollar,” and Nigeria with the “eNaira,” are testing CBDCs as tools to improve financial inclusion and reduce the costs of cross-border payments.

The motivations behind these projects are diverse. Some nations hope to reduce reliance on cash and enhance transaction traceability to fight tax evasion and illicit finance. Others view CBDCs as a strategic response to the growing influence of private cryptocurrencies and foreign digital payment systems. In both cases, central banks see digital currencies as an opportunity to regain control over the infrastructure of money in a rapidly evolving financial landscape.

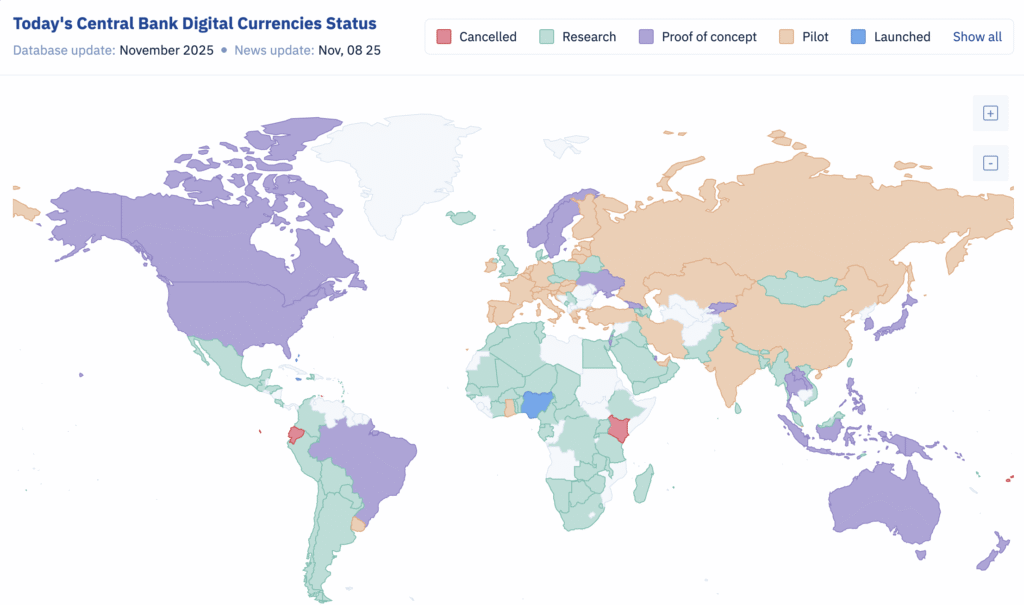

The spread of CBDC research and experimentation is now global, involving almost every major economy. The following map highlights how widespread these initiatives have become.

Over 130 countries, representing nearly 98 percent of global GDP, are developing or piloting a Central Bank Digital Currency. Data from the Atlantic Council CBDC Tracker shows that the majority of nations are in the research or proof-of-concept phase, while others like China and Nigeria have already launched pilot programs.

1.3 The Global Race for Digital Sovereignty

Beyond economic modernization, CBDCs have become instruments of geopolitical competition. The ability to issue and control a digital national currency is increasingly viewed as a matter of sovereignty and global influence.

China was among the first to recognize this potential. Through its e-CNY project, the country aims not only to digitize its domestic payments but also to lay the groundwork for an alternative international financial network that could reduce dependence on the US dollar. In response, the United States Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank have intensified their own research efforts to ensure they do not fall behind in this new monetary race.

Emerging economies are also joining the movement. For countries in Latin America or Africa, CBDCs represent a way to modernize payment systems, reach unbanked populations, and stabilize fragile financial sectors. However, they also introduce new vulnerabilities: reliance on digital infrastructure increases exposure to cyberattacks and technological failures, which can have serious economic consequences.

As this global experimentation unfolds, a new question arises: are we witnessing a financial revolution that will democratize access to money, or a new form of centralized control over the economy? The answer will depend on how CBDCs are designed and governed in the years to come.

II. How CBDCs Work: Promise, Design, and Controversies

2.1 The Technological and Monetary Foundations of CBDCs

At their core, Central Bank Digital Currencies are digital liabilities of the central bank, just like physical banknotes. However, the way they operate is far more complex. A CBDC exists entirely in electronic form and is typically issued to financial institutions or directly to the public through digital wallets. The architecture chosen by each central bank determines how the system functions and who interacts directly with the central authority.

Two main models are currently being explored: wholesale and retail CBDCs.

- Wholesale CBDCs are limited to use between banks and financial institutions. They aim to improve the efficiency of interbank settlements and cross-border transactions by reducing costs and settlement times.

- Retail CBDCs, on the other hand, are designed for the general public. Individuals and businesses could hold accounts or wallets directly linked to the central bank, allowing them to make payments without going through commercial banks.

The technological backbone of these systems can vary. Some central banks experiment with blockchain or distributed ledger technologies to ensure transparency and security, while others prefer centralized databases for greater control and scalability. The European Central Bank, for instance, has been cautious about using blockchain for the digital euro, focusing instead on ensuring stability, efficiency, and compliance with privacy laws.

This ambition reflects a broader trend in which central banks are reinventing their traditional role to maintain stability in an increasingly digital economy, a topic explored in more detail in The Role of Central Banks in Economic Stability.

This diversity of approaches reflects the delicate balance between innovation and control. Too much decentralization could weaken a central bank’s authority, but too much centralization might create public resistance and privacy concerns. Designing a CBDC that is both secure and trusted is therefore one of the greatest challenges policymakers face.

2.2 The Economic and Social Benefits of CBDCs

Supporters of CBDCs see them as a transformative innovation with the potential to modernize financial systems and promote inclusion. By providing a public digital payment option, central banks could ensure universal access to safe money even as cash usage declines. In many developing countries, where millions remain unbanked, CBDCs could allow citizens to hold digital funds without relying on commercial banks or costly intermediaries.

From a policy standpoint, CBDCs could also strengthen monetary transmission mechanisms. Since central banks would have a direct link to consumers, they could implement monetary measures, such as stimulus payments or interest rate adjustments, more effectively. During economic crises, this capability could make it easier to inject liquidity into households and small businesses without depending on slow or fragmented private channels.

CBDCs could also make cross-border payments faster and cheaper. Currently, international transactions often involve multiple intermediaries, leading to high fees and long processing times. With compatible CBDC systems, countries could enable instant cross-border transfers and reduce reliance on global payment networks dominated by private players.

Finally, CBDCs might enhance transparency and security. By offering a fully traceable and state-backed alternative to cash, governments could reduce tax evasion, money laundering, and the financing of illicit activities. These potential benefits explain why over 130 countries are now exploring or piloting CBDC projects, according to the Atlantic Council’s CBDC Tracker.

2.3 The Concerns: Privacy, Surveillance, and Financial Stability Risks

Despite their advantages, CBDCs raise significant economic, ethical, and technical challenges. One of the most pressing concerns is privacy. Unlike cash, which allows users to transact anonymously, digital currencies could enable governments to track every payment in real time. This capacity, while useful for combating crime, could easily turn into a tool for surveillance. Citizens might fear that their financial data could be monitored, misused, or even weaponized for political purposes.

Another major risk lies in financial stability. If people can hold funds directly at the central bank, they may withdraw their deposits from commercial banks, especially during times of crisis. This phenomenon, known as bank disintermediation, could weaken private banks and limit their ability to provide credit to the economy. To prevent such outcomes, central banks are considering limits on individual CBDC holdings or tiered interest rates that discourage mass transfers from bank accounts.

There are also serious cybersecurity and operational risks. A CBDC would represent a critical national infrastructure. A cyberattack or technical failure could have devastating consequences, disrupting payments, financial markets, and public trust in the currency. Ensuring resilience and protection against such threats is therefore essential.

Lastly, the introduction of CBDCs could alter the social contract of money. For centuries, cash has symbolized both economic participation and individual freedom. If that freedom becomes conditional on digital systems controlled by the state, the shift could have profound implications for civil liberties. Finding a balance between efficiency, transparency, and privacy will determine whether citizens ultimately accept or reject this new form of money.

III. The Future of Money: Coexistence or Cashless Society?

3.1 Will CBDCs Truly Replace Cash?

The prospect of a fully cashless society has fascinated economists and policymakers for years. In theory, Central Bank Digital Currencies could replace physical money entirely. They offer speed, traceability, and integration with the digital economy, all of which make them more efficient than coins and banknotes. For governments, eliminating cash could reduce illegal transactions, increase tax compliance, and make monetary policy easier to manage.

However, replacing cash is not simply a question of efficiency. Cash remains deeply tied to trust and personal autonomy. It allows individuals to transact privately, without relying on intermediaries or exposing personal data. For many, especially in rural areas or among older populations, cash also provides a sense of control that digital systems cannot replicate.

Moreover, a complete transition to CBDCs could create new forms of exclusion. Not everyone has access to smartphones, stable internet connections, or digital literacy. For this reason, most central banks, including the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, have emphasized that CBDCs are meant to complement, not replace, cash. The goal is to provide an alternative, not to force a revolution.

Nevertheless, history shows that technology tends to phase out older systems once adoption becomes widespread. If digital transactions become universal and trusted, cash may gradually lose relevance, much like checks or paper bills have in many economies. The key question is whether this process will be evolutionary and inclusive or disruptive and imposed.

3.2 Lessons from Current CBDC Experiments

The global experimentation with CBDCs provides valuable insight into what works and what does not. China’s digital yuan (e-CNY) remains the most advanced initiative. It has been integrated into popular apps and used for millions of transactions. Yet adoption remains limited compared to private payment platforms, as many users see little reason to switch from established digital methods.

In Nigeria, the introduction of the eNaira faced significant resistance. Many citizens distrusted the government’s motives or found the technology inconvenient. Adoption rates remained low, demonstrating that technological innovation alone is not enough to ensure public acceptance. The lesson is clear: a CBDC cannot succeed without trust, user-friendly design, and effective communication.

Conversely, Sweden’s e-krona offers an example of cautious progress. As one of the most cashless societies in the world, Sweden faces the risk of excluding those who still rely on cash. The e-krona project aims to strike a balance between innovation and inclusion, ensuring that citizens continue to have access to state-backed money in a digital form.

These case studies reveal a common pattern. The success of a CBDC depends not only on its technology but also on social confidence. People must believe that their data is safe, their money is accessible, and their government will not misuse its new power. Without that foundation of trust, even the most advanced digital currency will struggle to replace traditional cash.

3.3 The Road Ahead: Building a Digital yet Human-Centered Monetary System

As central banks continue their research and pilot programs, the future of money is gradually taking shape. It is unlikely that cash will disappear overnight, but its role will undoubtedly shrink as digital alternatives gain ground. The challenge for policymakers is to design a system that combines technological efficiency with human values such as privacy, accessibility, and fairness.

To achieve this, governments will need to collaborate internationally. A fragmented world of incompatible digital currencies could lead to inefficiency and economic friction. Institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) are already calling for common standards to ensure interoperability between CBDCs. Global coordination will be essential to prevent the emergence of digital monetary silos that mirror geopolitical divisions.

Public education will also play a decisive role. Citizens must understand how CBDCs work, what their benefits are, and how their data will be protected. Transparent communication can help prevent fears of surveillance or control from overshadowing the genuine advantages of a modernized monetary system.

Ultimately, CBDCs are not just a technological innovation. They represent a philosophical shift in the relationship between citizens, governments, and money. Whether this transformation leads to a more inclusive financial system or a more controlled one will depend on the principles guiding their implementation.

The future of money is digital, but its success will depend on how well it preserves what has always made money meaningful: trust, freedom, and human connection

Conclusion

Money has always evolved alongside society. From metal coins to paper notes, from credit cards to mobile payments, every transformation has reflected deeper changes in how people live, trade, and trust. Central Bank Digital Currencies are the next step in this long evolution. They promise to modernize monetary systems, enhance efficiency, and promote financial inclusion in an increasingly digital world.

Yet, as with every innovation, progress comes with trade-offs. The transition from physical to digital money raises questions that go beyond technology or economics. It touches on freedom, privacy, and public trust — values that have defined money’s social role for centuries. While CBDCs could make payments faster and safer, they also risk concentrating power in the hands of central authorities and reducing the anonymity that cash provides.

For this reason, the real debate is not whether CBDCs can replace cash, but whether they should. A purely cashless society may be efficient, but efficiency alone does not guarantee fairness or liberty. The challenge for policymakers is to design CBDCs that serve citizens rather than control them, ensuring that innovation strengthens, rather than undermines, public confidence in money.

In the end, the most likely future is one of coexistence. Cash may lose ground, but it will not vanish overnight. Instead, it will stand alongside digital currencies as a symbol of choice — the freedom to transact both privately and electronically. The ultimate success of CBDCs will depend not only on their technical sophistication, but on their ability to preserve that choice and the trust that underpins it.

The question, then, is not whether digital money will arrive. It already has. The question is what kind of digital money we want and what kind of society we are willing to build around it.