Table of contents

ToggleIntroduction

By 2050, one in six people in the world will be over the age of 65, according to the United Nations. This unprecedented demographic shift is reshaping not only societies but also the very foundations of the global economy. Economists have long studied the usual drivers of inflation—monetary policy, commodity shocks, and demand cycles—but today, an increasingly pressing question emerges: could aging itself become the silent force taming price growth?

The idea may sound counterintuitive. On one hand, aging populations consume less, save more, and weaken aggregate demand—classic ingredients for disinflation or even deflation. On the other, shrinking workforces, rising healthcare costs, and strained pension systems could exert new inflationary pressures. The outcome is far from straightforward, and the experience of countries like Japan, Europe, and soon China suggests that demographics might become one of the defining forces in economic policymaking.

This article explores the intersection between demographics and inflation, examining whether aging truly acts as an “inflation killer” or whether its impact is more complex. By analyzing historical cases, economic mechanisms, and future policy options, we aim to understand how the gray wave could reshape the global economy in the decades to come.

I. The Demographic Shift: Understanding Aging Economies

1.1. The Global Demographic Transformation

Demographics have always shaped economies, but today the world faces a structural change without precedent. Fertility rates are falling in almost every region, and life expectancy continues to rise thanks to medical advances, better nutrition, and improved living conditions. According to the United Nations World Population Prospects (2022), the global median age has increased from 21.5 years in 1970 to over 30 years today, and it is projected to surpass 40 years in developed economies by mid-century (UN WPP, 2022)

This shift manifests in the so-called “inverted pyramid” problem: more retirees relative to workers. Whereas post-war societies enjoyed wide population bases with many young workers supporting fewer elders, today the dependency ratio—the number of retirees per active worker—is climbing steadily. In countries like Japan, Italy, and Germany, fewer than three workers support one retiree, a ratio expected to worsen dramatically.

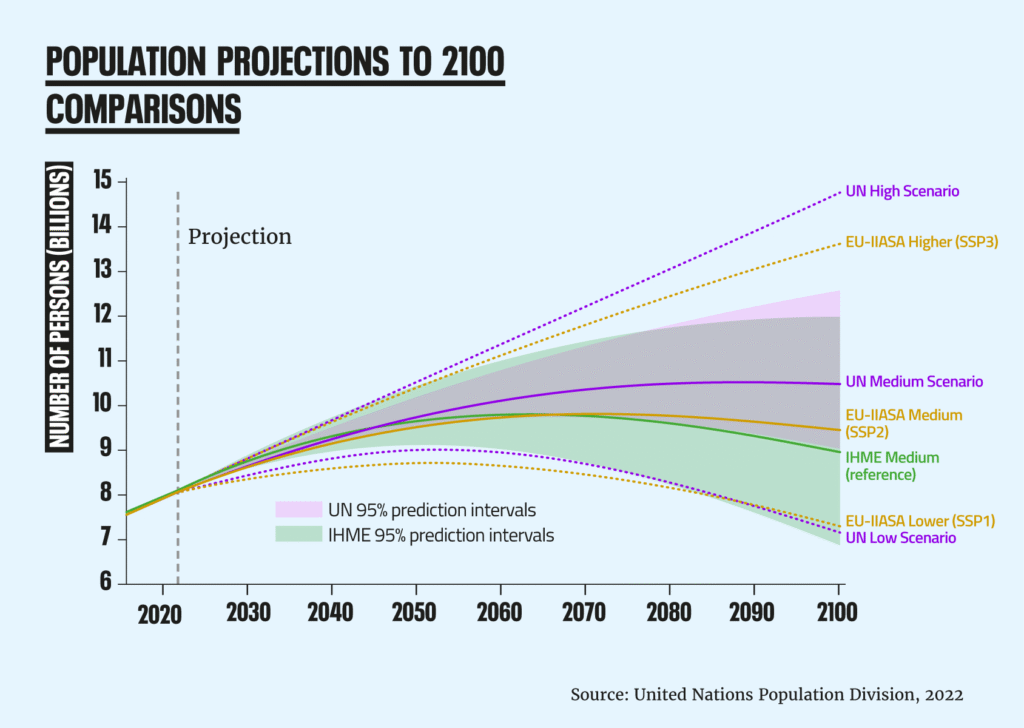

While the world’s population is projected to rise until mid-century, the long-term outlook is far less certain. The UN’s medium scenario suggests stabilization around 10.4 billion people, but alternative forecasts — such as the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) or the EU-IIASA models — show possible peaks followed by decline. The implication for the global economy is profound: even if total population continues to grow, the age structure will shift dramatically, with far fewer working-age individuals relative to retirees. In other words, population growth does not automatically translate into economic dynamism; what matters is who makes up that population.

These demographic changes raise fundamental questions for economic stability. With fewer young consumers entering the labor market and more elderly people living longer, the very engines of growth and inflation are being recalibrated.

Read our article on Inflation here.

1.2. Historical Perspective: Demographic Dividends and Slowdowns

Looking backward offers critical insight into the future. Demographics have historically played a crucial role in shaping growth, savings, and inflation patterns.

- The post-war baby boom (1950s–1970s): High fertility rates created a young and dynamic labor force. This “demographic dividend” supported rapid industrial growth, rising wages, and robust consumer demand, contributing to both economic expansion and, in many cases, inflationary pressures. In the United States, for example, the baby boom coincided with a long period of robust demand and higher inflation episodes, particularly during the oil shocks of the 1970s.

- Japan’s lost decades (1990s–2020s): In contrast, Japan became the first major economy to face rapid population aging combined with low fertility. By the 1990s, the demographic dividend had turned into a demographic drag. Fewer young workers and more retirees contributed to stagnating growth, persistent low inflation, and even bouts of deflation. Despite aggressive monetary policy, Japan’s aging demographics created structural headwinds that central banks alone could not counter.

- Europe’s path: Several European countries are now following Japan’s trajectory. Italy and Germany, with some of the lowest fertility rates in the world, are seeing labor shortages, weaker consumption growth, and subdued inflation trends.

This historical contrast highlights the potential of demographics as a structural determinant of inflationary or disinflationary pressures. When populations are young and expanding, economies tend to grow fast and inflation risks are higher. When populations age, consumption patterns shift, savings accumulate, and inflation can lose momentum.

1.3. Current Outlook Across Regions

The demographic story is not uniform. Different regions face very different futures:

- Developed Economies (Japan, Europe, United States):

Japan remains the textbook case of an aging society, with more than 28% of its population over 65. Europe is not far behind: countries like Italy, Spain, and Germany are entering a similar phase, with dependency ratios climbing rapidly. The United States, while aging more slowly due to immigration and slightly higher fertility, is also on this path. For these economies, the big challenge lies in financing pensions and healthcare systems while sustaining economic dynamism. - Emerging Asia (China, South Korea):

The “demographic dividend” that powered China’s economic miracle is fading. The one-child policy has left a shrinking workforce, and the population declined for the first time in 2022. By 2050, nearly 40% of Chinese citizens will be over 60. South Korea, meanwhile, has the world’s lowest fertility rate (0.7 children per woman), setting the stage for even sharper demographic decline. For these nations, aging will arrive before they are fully “rich,” creating economic and social challenges distinct from those of the West. - Africa: The demographic exception:

In stark contrast, Africa’s population is booming, with the median age still below 20 in many countries. Nigeria, projected to become the world’s third-most populous country by 2050, could benefit from a demographic dividend if institutions and policies harness the growing workforce effectively. However, this youth bulge could also lead to instability if jobs and infrastructure lag behind population growth.

These divergent demographic paths imply different inflationary dynamics across regions. Aging in developed and Asian economies could suppress inflationary pressures, while young and growing populations in Africa and parts of South Asia may fuel higher demand-driven inflation.

II. The Economic Mechanisms Linking Aging to Inflation

2.1. Demand-Side Pressures

Aging populations transform the way societies consume, and these shifts directly affect inflation dynamics.

Lower spending on durable goods:

Younger populations typically drive demand for housing, cars, technology, and other durable goods — purchases that tend to stimulate both growth and inflation. As societies age, however, the consumption profile changes. Retirees generally spend less on such goods and more on services like healthcare, leisure, and basic necessities. This leads to a flattening of aggregate demand, weakening one of the traditional drivers of price increases.

Healthcare and services as dominant sectors:

While older populations consume more medical care and personal services, these expenditures often grow at a slower and more predictable pace than the demand surges driven by younger consumers. Moreover, technological improvements in healthcare delivery can offset cost pressures, although in many cases rising demand has outpaced efficiency gains.

Weaker labor force participation and productivity:

Another demand-side factor lies in the link between demographics and productivity. As large cohorts retire, economies lose experienced workers. If younger, less numerous generations cannot replace this productive capacity, long-term output growth slows. Slower growth translates into weaker aggregate demand, reinforcing disinflationary pressures.

Case study – Japan:

Japan illustrates this dynamic vividly. Since the 1990s, an aging population combined with subdued consumption has contributed to decades of low inflation, despite repeated efforts by the Bank of Japan to reignite price growth through ultra-loose monetary policy. The demand-side drag of demographics proved to be a structural headwind.

2.2. Supply-Side Constraints

While demand may weaken with aging, supply-side effects push in the opposite direction, creating potential inflationary risks.

Labor shortages and wage pressures:

As workforces shrink, employers face difficulties in filling positions. This can drive up wages, particularly in sectors that cannot easily automate or outsource, such as healthcare, construction, or services. In theory, rising wages feed into higher costs for businesses, which may then pass them on to consumers in the form of higher prices.

- For example, in Germany and Italy, shortages of skilled labor are already becoming a structural challenge. Immigration has mitigated the problem somewhat, but demographic decline suggests continued upward wage pressure.

- In the United States, despite slower aging compared to Europe, the labor market has tightened in sectors like healthcare and logistics, where demographics are an important factor.

Rising healthcare and pension costs:

Aging societies inevitably devote a larger share of GDP to pensions and healthcare. Governments either raise taxes, borrow more, or reallocate spending to cover these costs. All three options carry inflationary risks:

- Higher taxes may increase labor costs.

- Higher borrowing could stoke demand and push interest rates higher.

- Reduced spending in other areas may lower investment, constraining supply.

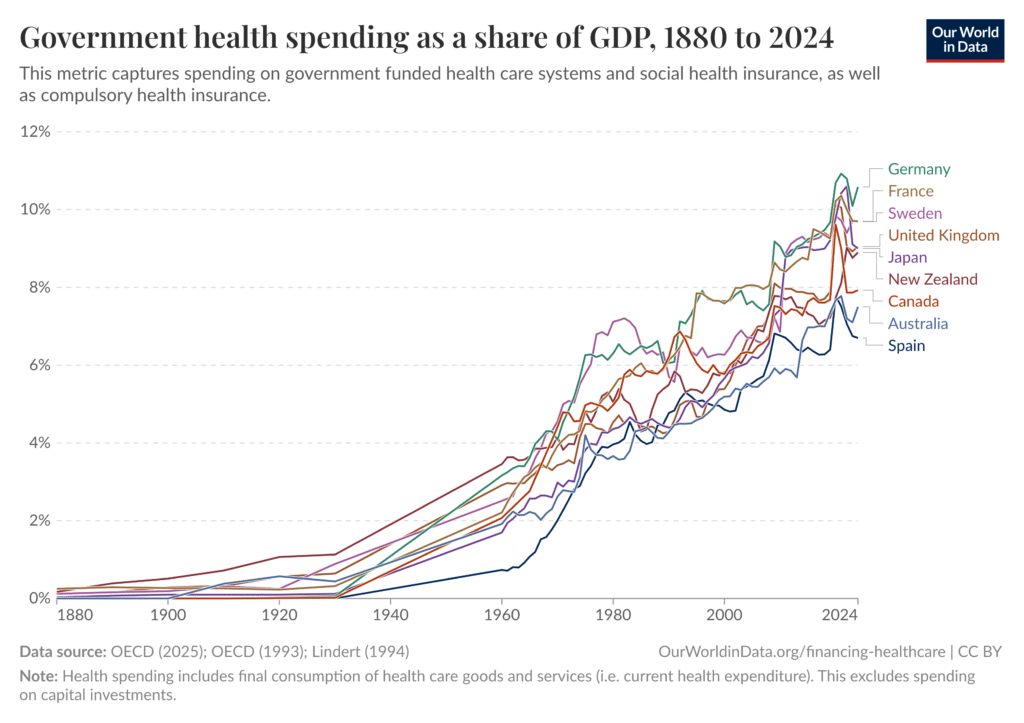

Health spending has steadily climbed over the past century, rising from less than 1% of GDP in most advanced economies in 1900 to between 8–12% today. This long-term trend highlights how aging populations place growing fiscal demands on governments, particularly in countries like Germany, France, and Japan. While higher health spending reflects improved care and longevity, it also creates structural pressures on public finances. As societies continue to age, these costs are unlikely to stabilize, raising the risk of fiscal imbalances and, in some cases, inflationary financing if tax revenues cannot keep up.

Dependency ratios and fiscal stress:

The fiscal implications of aging are profound. As the ratio of retirees to workers rises, governments face pressure to expand transfers (pensions, healthcare) while the tax base shrinks. This creates chronic deficits that can push states toward inflationary financing if debt levels become unsustainable.

Energy and housing implications:

A less obvious supply-side dimension is infrastructure. Aging societies may require different housing, transport, and energy solutions. If supply does not adjust smoothly, mismatches can lead to localized inflation (for example, rising healthcare-related construction or specialized housing costs).

2.3. Savings, Investment, and Monetary Dynamics

Perhaps the most complex channel linking demographics and inflation lies in savings and investment behavior.

The life-cycle hypothesis:

Economists often refer to the “life-cycle hypothesis,” which suggests that individuals save during their working years and dissave (spend down savings) in retirement. When applied to entire societies, this creates structural cycles:

- High savings phase: When a large share of the population is of working age, aggregate savings rise. More savings translate into abundant capital supply, lower interest rates, and disinflationary tendencies.

- Dissaving phase: As retirees increase, they begin to spend down their savings. This can reduce capital supply, put upward pressure on interest rates, and potentially generate inflationary forces.

Which dominates?

This is hotly debated. Some argue aging will keep pushing interest rates lower because risk-averse retirees hold onto savings and invest in safe assets. Others suggest that as baby boomers retire en masse, dissaving will lead to higher interest rates and possibly inflation. The outcome depends on how fast retirees draw down wealth, and whether younger generations are numerous enough to offset the imbalance.

Impact on monetary policy:

Aging also complicates the role of central banks. For instance:

- In Japan, the Bank of Japan has struggled to generate inflation despite decades of ultra-loose policy, largely because demographics anchor demand.

- In Europe, the European Central Bank faces a similar demographic headwind, limiting the effectiveness of its inflation-targeting strategies.

- In the United States, a relatively younger demographic profile has allowed the Federal Reserve to sustain higher growth and inflation, but the gap is narrowing as baby boomers retire.

Global capital flows:

Aging is not synchronized globally, which means capital moves across borders. Older economies like Japan and Europe export savings to younger, faster-growing regions. This keeps global interest rates lower than they might otherwise be, spreading disinflationary forces worldwide. But as emerging giants like China also age, the global “savings glut” could fade, changing the picture dramatically.

III. The Future: Aging, Inflation, and Policy Choices

3.1. Will Aging Always Suppress Inflation?

At first glance, the evidence from Japan and much of Europe suggests that aging is inherently disinflationary. Older populations consume less, invest conservatively, and create excess savings — all forces that suppress demand and prices. But the picture is not so simple. Aging also brings inflationary risks that could emerge more strongly in the future.

The case for aging as an “inflation killer”:

- Weaker consumption growth: With retirees spending less on durable goods, economies lose the high-octane demand that younger societies generate.

- Capital abundance: As long as retirees preserve rather than liquidate their savings, financial markets are flush with capital, which depresses interest rates and borrowing costs.

- Structural stagnation: The combination of slow growth, weak investment, and cautious spending tends to anchor inflation at low levels.

Counter-arguments — why aging could drive inflation instead:

- Labor shortages: As workforces shrink, wage pressures intensify. In sectors like healthcare or construction, these pressures are hard to offset with technology alone.

- Fiscal imbalances: Pension and healthcare spending are set to surge in aging societies. If governments resort to debt monetization or loose fiscal policy, inflationary risks grow.

- Dissaving dynamics: Once retirees begin to draw down savings in earnest, the global savings glut could reverse, pushing up interest rates and prices.

In short, aging is not a one-directional force. The outcome depends on the interplay between demand-side weakness and supply-side bottlenecks.

3.2. The Role of Technology and Globalization

Demographics alone do not determine the future. Technology and globalization — or their retreat — will be decisive in shaping how aging translates into inflationary outcomes.

Technology as a demographic buffer:

- Automation and AI: Robotics, artificial intelligence, and digital tools can offset the shrinking labor supply by boosting productivity. Japan has pioneered the use of robots in manufacturing and even elderly care, showing how technology can mitigate demographic constraints.

- Healthcare innovation: Advances in biotechnology, telemedicine, and pharmaceuticals may reduce the cost burden of aging populations, easing fiscal and inflationary pressures.

- Remote work and efficiency gains: Older workers can remain productive longer if flexible work arrangements are widespread, softening the labor shortage dynamic.

Globalization and its retreat:

- Past globalization effects: Over the past three decades, globalization acted as a strong disinflationary force. Cheap labor from China and other emerging economies held down global prices, even as advanced economies aged.

- Deglobalization risks: Today, geopolitical tensions, protectionist policies, and the shift toward “friend-shoring” threaten to reverse this effect. If supply chains fragment and labor arbitrage diminishes, the inflation-suppressing power of globalization may fade — just as aging accelerates in emerging economies.

- The China factor: For decades, China’s vast young workforce exported disinflation to the world. But with China itself now aging rapidly, this effect will diminish, raising questions about whether the global economy can still rely on cheap supply chains to offset demographic stagnation in advanced nations.

In other words, technology may counter aging’s inflationary risks, while deglobalization could amplify them. The balance between these two forces will be pivotal.

3.3. Policy Responses for Aging Economies

Demographics are not destiny. Policy choices can shape whether aging societies face deflation, stable prices, or inflationary stress.

- Immigration policies:

One straightforward way to mitigate demographic decline is to attract younger workers from abroad. The United States has historically benefited from immigration, which has slowed its aging compared to Europe and Japan. However, political resistance to immigration remains strong in many countries, limiting its potential. Without immigration, aging economies risk deeper labor shortages and slower growth. - Pension and retirement reforms:

Extending working lives is another option. Raising the retirement age, linking pensions to life expectancy, or incentivizing part-time work among seniors can ease fiscal pressure while keeping experienced workers in the labor market. France, for instance, has already implemented controversial pension reforms, and similar debates are ongoing across Europe. - Boosting labor force participation:

Policies that encourage greater participation by underrepresented groups — women, older workers, or immigrants — can soften demographic headwinds. Flexible childcare policies, gender equality measures, and retraining programs all play a role. - Innovation and productivity strategies:

Governments can invest in technology, education, and infrastructure to boost productivity, compensating for fewer workers. As aging erodes labor supply, only higher productivity can sustain economic growth without inflationary imbalances. - Healthcare system reforms:

Containing healthcare costs is crucial. Aging societies that fail to modernize healthcare systems may face exploding public spending, which could force inflationary fiscal policies. Innovations like preventive care, AI diagnostics, and telemedicine can reduce these risks. - Monetary and fiscal coordination:

Central banks alone cannot offset demographic forces. In aging societies, ultra-low interest rates may fail to generate inflation (as seen in Japan). Coordinated fiscal policy — such as targeted investment and structural reforms — is essential to complement monetary tools. The balance will be delicate: too much fiscal expansion risks inflation; too little may lock economies into stagnation.

Policy frameworks matter enormously: the OECD highlights that labor market participation, pension reform, and immigration policies are essential to mitigate the economic effects of population ageing (OECD, 2023)

Conclusion

Demographics are no longer a silent backdrop to economic policy — they are emerging as one of the defining forces shaping growth, stability, and inflation in the 21st century. As populations age, the traditional drivers of price dynamics are being reconfigured. On the one hand, weaker demand, higher savings, and slower consumption growth suggest that aging acts as a natural “inflation killer.” On the other, shrinking labor forces, rising healthcare and pension costs, and mounting fiscal pressures introduce the possibility of new inflationary waves.

The lessons of history are instructive. Japan shows how aging can anchor economies in low inflation for decades, despite aggressive monetary stimulus. Yet the future may not simply replicate Japan’s path. Unlike the 1990s, the world now faces simultaneous demographic aging across advanced and emerging economies, combined with forces like deglobalization, technological disruption, and fiscal experimentation. These interactions will determine whether aging suppresses inflation or fuels it.

Policymakers still have agency. Immigration, pension reforms, and productivity-boosting innovation can mitigate demographic headwinds. Healthcare reforms and responsible fiscal management can prevent inflationary imbalances. Above all, technology — from AI to robotics — holds the potential to counter the supply-side pressures of aging, while globalization’s uncertain trajectory will either reinforce or undermine its disinflationary role.

The central question — is aging the new inflation killer? — does not have a single answer. In some contexts, yes: aging suppresses demand and anchors prices. In others, particularly where fiscal stress and labor shortages dominate, the gray wave may instead fuel inflation. What is certain, however, is that demographics will increasingly shape the economic landscape, forcing policymakers, investors, and businesses to adapt to a world where the age structure of societies is as critical to inflation as oil shocks or central bank decisions once were.